NASA's Chandra Identifies an Underachieving Black Hole

Submitted by chandra on Thu, 2024-03-21 09:39

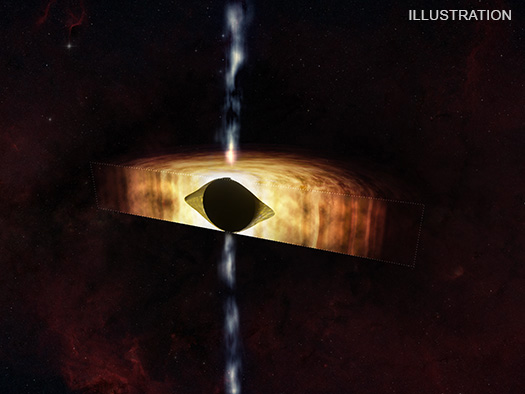

Quasar H1821+643

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Nottingham/H. Russell et al.; Radio: NSF/NRAO/VLA; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

This image shows a quasar, a rapidly growing supermassive black hole, which is not achieving what astronomers would expect from it, as reported in our latest press release. Data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory (blue) and radio data from the NSF’s Karl G. Jansky’s Very Large Array (red) reveal some of the evidence for this quasar’s disappointing impact on its host galaxy.

Known as H1821+643, this quasar is about 3.4 billion light-years from Earth. Quasars are a rare and extreme class of supermassive black holes that are furiously pulling material inwards, producing intense radiation and sometimes powerful jets. H1821+643 is the closest quasar to Earth in a cluster of galaxies.

Quasars are different than other supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxy clusters in that they are pulling in more material at a higher rate. Astronomers have found that non-quasar black holes growing at moderate rates influence their surroundings by preventing the intergalactic hot gas from cooling down too much. This regulates the growth of stars around the black hole.

Chandra Ties Powerful Black Hole to Stellar Beads-on-a-String

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2024-02-21 12:05

Osase Omoruyi with her parents’ favorite beads.

We are happy to welcome Osase Omoruyi as a guest blogger. Osase is the first author of the paper that is the focus of our latest press release, and is an NSF Graduate Research Fellow at Harvard University, where she is currently completing her PhD in Astronomy and Master’s in History of Science. Osase uses a variety of telescopes, from X-ray through Radio, as well as computer simulations, to study the fascinating life of galaxies. She is particularly interested in how stars and black holes, which are small in comparison to the scale of a whole galaxy, can transform how galaxies change over time.

In 2008, astronomers using the Wisconsin–Indiana–Yale NOAO (WIYN) telescope in Arizona published images of the newly discovered galaxy cluster named SDSS J1531+3414 (SDSS J1531 for short). At first glance, it seemed like a standard massive cluster of galaxies with one giant galaxy in its center, hundreds of others surrounding it, and arc-like structures caused by gravitational lensing – a phenomenon where the cluster's gravity bends light from galaxies behind it.

However, our understanding of SDSS J1531 changed dramatically in 2014 when the Hubble Space Telescope provided a higher-resolution view of the cluster from space. Contrary to initial beliefs, the heart of the cluster housed not one but two massive galaxies, on course to collide and merge into a single entity. They also featured 19 clusters of young stars wrapped around them in a pattern that resembled beads on a string.

Stellar Beads on a String

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2024-02-21 09:52

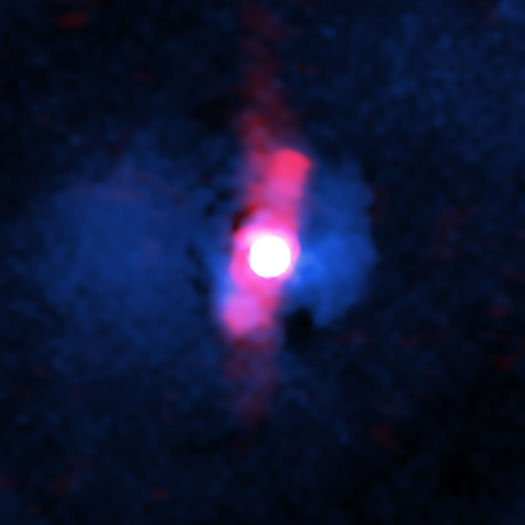

SDSS J1531+3414

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/O. Omoruyi et al.; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI/G. Tremblay et al.;

Radio: ASTRON/LOFAR; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

Astronomers have discovered one of the most powerful eruptions from a black hole ever recorded in the system known as SDSS J1531+3414 (SDSS J1531 for short). As explained in our press release, this mega-explosion billions of years ago may help explain the formation of a striking pattern of star clusters around two massive galaxies, resembling “beads on a string.”

SDSS J1531 is a massive galaxy cluster containing hundreds of individual galaxies and huge reservoirs of hot gas and dark matter. At the center of SDSS J1531, which is located about 3.8 billion light-years away, two of the cluster’s largest galaxies are colliding with each other.

Astronomers used several telescopes to study SDSS J1531 including NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR), a radio telescope. This composite image shows SDSS J1531 in X-rays from Chandra (blue and purple) that have been combined with radio data from LOFAR (dark pink) as well as an optical image from the Hubble Space Telescope (appearing as yellow and white). The inset gives a close-in view of the center of SDSS J1531 in optical light, showing the two large galaxies and a set of 19 large clusters of stars, called superclusters, stretching across the middle. The image shows these star clusters are arranged in an ‘S’ formation that resembles beads on a string.

Telescopes Show the Milky Way's Black Hole is Ready for a Kick

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2024-02-07 17:55This artist’s illustration depicts the findings of a new study about the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy called Sagittarius A* (abbreviated as Sgr A*). As reported in our latest press release, this result found that Sgr A* is spinning so quickly that it is warping spacetime — that is, time and the three dimensions of space — so that it can look more like a football.

These results were made with NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the NSF’s Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). A team of researchers applied a new method that uses X-ray and radio data to determine how quickly Sgr A* is spinning based on how material is flowing towards and away from the black hole. They found Sgr A* is spinning with an angular velocity that is about 60% of the maximum possible value, and with an angular momentum of about 90% of the maximum possible value.

NASA's IXPE Helps Researchers Maximize 'Microquasar' Findings

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2024-01-17 10:10

SS 433

Credit: X-ray: (IXPE): NASA/MSFC/IXPE; (Chandra): NASA/CXC/SAO; (XMM): ESA/XMM-Newton; IR: NASA/JPL/Caltech/WISE; Radio: NRAO/AUI/NSF/VLA/B. Saxton. (IR/Radio image created with data from M. Goss, et al.); Image Processing/compositing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk & K. Arcand

This composite image of the Manatee Nebula captures the jet emanating from SS 433, a black hole pulling material inwards that is embedded in the supernova remnant which spawned it. Radio emission from the supernova remnant are blue-green, whereas the X-ray from IXPE, XMM-Newton and Chandra are highlighted in bright blue-purple and pink-white set against a backdrop of infrared data in red. The black hole emits twin jets of matter traveling in opposite directions at nearly the speed of light.

These jets distort the remnant’s shape into one astronomers dubbed the Manatee. The jets become bright about 100 light-years away from the black hole, where particles are accelerated to very high energies by shocks within the jet. The IXPE data shows that the magnetic field, which plays a key role in how particles are accelerated, is aligned parallel to the jet — aiding our understanding of how astrophysical jets accelerate these particles to high energies.

NASA Telescopes Discover Record-Breaking Black Hole

Submitted by chandra on Mon, 2023-11-06 09:08

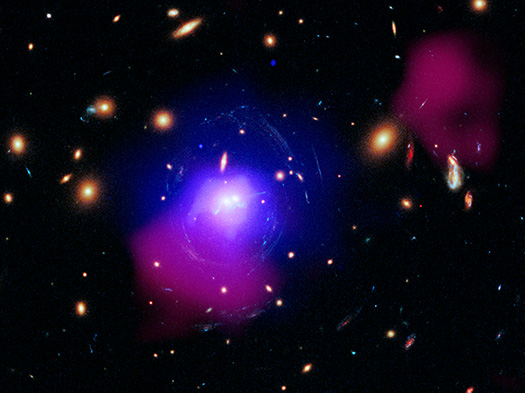

UHZ1

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO/Ákos Bogdán; Infrared: NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI; Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare & K. Arcand

This image contains the most distant black hole ever detected in X-rays, a result that may explain how some of the first supermassive black holes in the universe formed. As we report in our press release, this discovery was made using X-rays from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory (purple) and infrared data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (red, green, blue).

The extremely distant black hole is located in the galaxy UHZ1 in the direction of the galaxy cluster Abell 2744. The galaxy cluster is about 3.5 billion light-years from Earth. Webb data, however, reveal that UHZ1 is much farther away than Abell 2744. At some 13.2 billion light-years away, UHZ1 is seen when the universe was only 3% of its current age.

Chandra Studies a Moderately Massive Star Destroyed by a Giant Black Hole In Another Galaxy

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2023-08-16 11:00We are happy to welcome Dr. Brenna Mockler as our guest blogger. Brenna is a postdoctoral fellow at Carnegie Observatories in Pasadena. Her research is primarily on high-energy transients, with a focus on learning about the supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies and the environments they live in. Prior to her current position, she was a UC Chancellor's fellow at UCLA. She earned her PhD in Astronomy & Astrophysics from the University of California at Santa Cruz in 2022, and a bachelor's degree in Physics from Cornell University in 2016.

At the center of most large galaxies lies a supermassive black hole, larger than our solar system and millions to billions of times more massive than our Sun. These giant black holes influence the evolution of the entire galaxy — for example, they are thought to regulate star formation and their mass is strongly correlated with the mass of the galaxy. Supermassive black holes live in ‘galactic nuclei’ — dense, extreme environments, packed with thousands to millions of times the density of stars that we see in our own night sky.

While we can estimate the bulk characteristics of these nuclei, it is challenging to measure the individual components that make them up. Because there are so many stars packed so closely together, it is very difficult to pick out the unique characteristics of each star. Imagine you are out in the suburbs staring at a distant city skyline — you can tell there is a lot of light, but you can’t pick out the details of each individual lamppost and billboard. However, occasionally one of these stars will pass too close to the supermassive black hole at the center, and get ripped apart by the tidal forces from the black hole in a “tidal disruption event” (TDE).

Studies of Past X-ray Flares from Sgr A*

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2023-06-21 13:35In a new Nature paper astronomers have reported exciting evidence that the supermassive black hole at the center of our Galaxy, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A* for short), produced an intense flare of X-rays about 200 years ago. Sgr A* is 28,000 light-years from Earth, but even from this considerable distance, if a similar flare occurred today then X-ray telescopes like IXPE and Chandra may be damaged if they looked at Sgr A*.

Currently Sgr A* shows frequent but weak outbursts, and has been referred to as a “sleeping giant” by members of the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration.

In the new study astronomers learned about Sgr A*’s past outbursts by observing X-rays from clouds of gas around the supermassive black hole. While the primary X-rays from previous outbursts would have reached Earth in the past, X-rays reflected from clouds of gas will take a longer path and can arrive in time to be recorded by telescopes like Chandra and IXPE. This idea goes back decades, with the astronomers referring to a paper published in 1980. In the 1990s, several papers reported evidence for X-ray flares from the center of the Galaxy, including one in 1996 titled “ASCA View of Our Galactic Center: Remains of Past Activities in X-Rays?”.

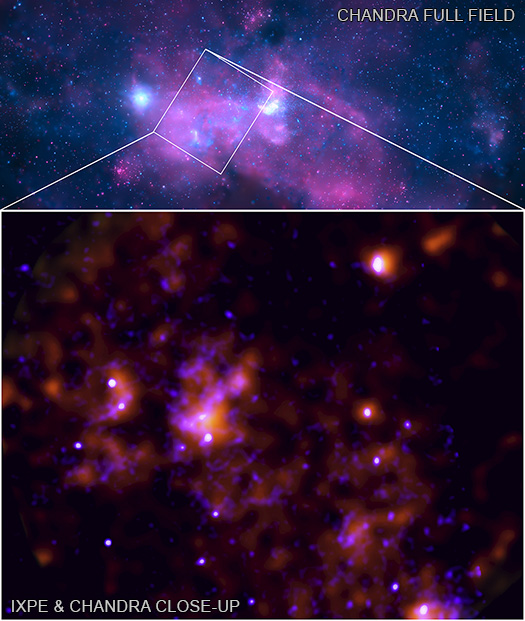

Milky Way's Central Black Hole Woke Up 200 Years Ago, NASA's IXPE Finds

Submitted by chandra on Fri, 2023-06-16 17:24

Sagittarius A* / Galactic Center

Credit: Chandra: NASA/CXC/SAO; IXPE: NASA/MSFC/F. Marin et al; Image Processing: L.Frattare, J.Major & K.Arcand; Sonification: NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)

These images show X-ray data of the area around the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. New data from NASA’s Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) has provided evidence that this black hole — known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) — had an outburst about 200 years ago after devouring gas and dust within its reach.

A Pair of Merging Galaxies Ignite Black Holes on a Collision Course

Submitted by chandra on Wed, 2023-04-05 10:58

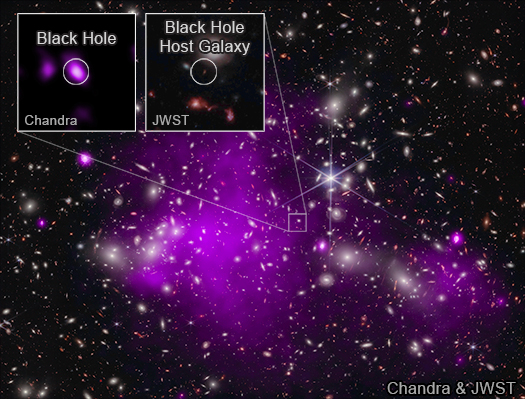

Artist's Illustration of Dual Quasar J0749+2255

Artwork Credit: NASA, ESA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI) Science Credit: NASA, ESA, Yu-Ching Chen (UIUC), Hsiang-Chih Hwang (IAS), Nadia Zakamska (JHU), Yue Shen (UIUC)

Quasars are among the universe's brightest fireworks. Scattered all across the sky, they blaze with the opulence of over 100 billion stars. And, like a brilliant July 4th aerial flare, they are dazzling for a relatively brief time — on cosmic timescales. That's because they're powered by voracious supermassive black holes gobbling up a lot of gas and dust that gets heated to high temperatures. But the quasar food buffet lasts only so long.

This fleeting characteristic of quasars helped astronomers find two quasars on a collision course with each other. They are embedded inside a pair of galaxies that smashed into each other 10 billion years ago. It's rare to find such a dynamic duo in the far universe. The detection yields clues as to how unsettled the cosmos was long ago, when galaxies more frequently collided and black holes were engorged with flotsam and jetsam from the close encounters.

Pages

Please note this is a moderated blog. No pornography, spam, profanity or discriminatory remarks are allowed. No personal attacks are allowed. Users should stay on topic to keep it relevant for the readers.

Read the privacy statement