For Release: Jan 18, 2018

McGill

Afterglow from cosmic smash-up continues to brighten, confounding expectations

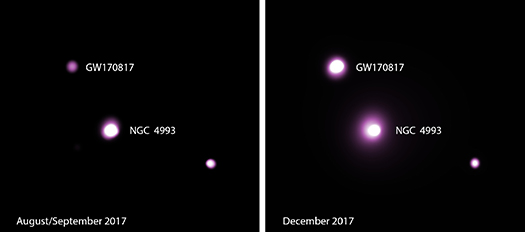

Credit: NASA/CXC/McGill University/J. Ruan et al.

The afterglow from the distant neutron-star merger detected last August has continued to brighten – much to the surprise of astrophysicists studying the aftermath of the massive collision that took place about 138 million light years away and sent gravitational waves rippling through the universe.

New observations from NASA's orbiting Chandra X-ray Observatory, reported in Astrophysical Journal Letters, indicate that the gamma ray burst unleashed by the collision is more complex than scientists initially imagined.

"Usually when we see a short gamma-ray burst, the jet emission generated gets bright for a short time as it smashes into the surrounding medium – then fades as the system stops injecting energy into the outflow," says McGill University astrophysicist Daryl Haggard, whose research group led the new study. "This one is different; it's definitely not a simple, plain-Jane narrow jet."

Cocoon theory

The new data could be explained using more complicated models for the remnants of the neutron star merger. One possibility: the merger launched a jet that shock-heated the surrounding gaseous debris, creating a hot 'cocoon' around the jet that has glowed in X-rays and radio light for many months.

The X-ray observations jibe with radio-wave data reported last month by another team of scientists, which found that those emissions from the collision also continued to brighten over time.

Credit: NASA/CXC/McGill University/J. Ruan et al.

While radio telescopes were able to monitor the afterglow throughout the fall, X-ray and optical observatories were unable to watch it for around three months, because that point in the sky was too close to the Sun during that period.

"When the source emerged from that blind spot in the sky in early December, our Chandra team jumped at the chance to see what was going on," says John Ruan, a postdoctoral researcher at the McGill Space Institute and lead author of the new paper. "Sure enough, the afterglow turned out to be brighter in the X-ray wavelengths, just as it was in the radio."

Physics puzzle

That unexpected pattern has set off a scramble among astronomers to understand what physics is driving the emission. "This neutron-star merger is unlike anything we've seen before," says Melania Nynka, another McGill postdoctoral researcher. "For astrophysicists, it's a gift that seems to keep on giving." Nynka also co-authored the new paper, along with astronomers from Northwestern University and the University of Leicester.