For Release: April 20, 2022

NASA/CXC

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Washington State Univ./V. Baldassare et al.; Optical: NASA/ESA/STScI

Press Image, Caption, and Videos

In some of the most crowded parts of the universe, black holes may be tearing apart thousands of stars and using their remains to pack on weight. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, could help answer key questions about an elusive class of black holes.

While astronomers have previously found many examples of black holes tearing stars apart, little evidence has been seen for destruction on such a large scale. This kind of stellar demolition could explain how mid-sized black holes are made through the runaway growth of a much smaller black hole.

Astronomers have made detailed studies of two distinct classes of black holes. The smaller variety are "stellar-mass" black holes that typically weigh 5 to 30 times the mass of the Sun. On the other end of the spectrum are the supermassive black holes that live in the middle of most large galaxies, weighing millions or even billions of solar masses. In recent years, there has also been evidence that an in-between class called "intermediate-mass" black holes exists.

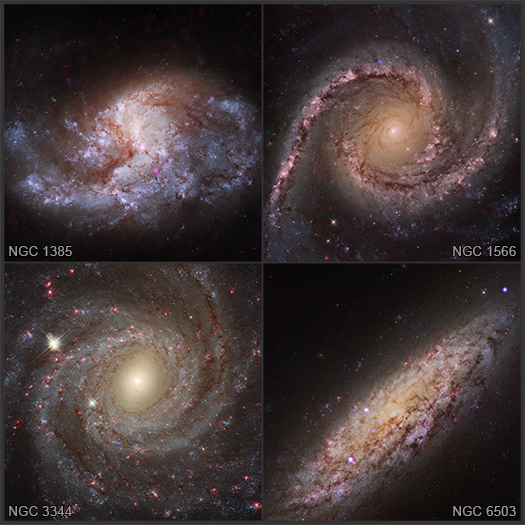

The latest study, using Chandra data of dense star clusters in the centers of 108 galaxies, provides evidence about where these mid-sized black holes might form and how they grow.

"When stars are so close together like they are in these extremely dense clusters, it provides a viable breeding ground for intermediate-mass black holes," said Vivienne Baldassare of Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, who led the study. "And it seems that the denser the star cluster, the more likely it is to contain a growing black hole."

Theoretical work by the team implies that if the density of stars in a cluster — the number packed into a given volume — is above a threshold value, a stellar-mass black hole at the center of the cluster will undergo rapid growth as it pulls in, shreds, and ingests the abundant stars in close proximity.

Of the clusters in the new Chandra study, the ones with density above this threshold were about twice as likely to contain a growing black hole as the ones below the density threshold. The density threshold depends also on how quickly the stars in the clusters are moving.

"This is one of the most spectacular examples we've seen of the insatiable nature of black holes, because thousands or tens of thousands of stars can be consumed during their growth," said Nicholas C. Stone, a co-author from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. "The runaway growth only begins slowing down once the supply of stars starts to run dry."

Other ways scientists have considered massive black holes at the centers of galaxies could form include the collapse of a gigantic cloud of gas and dust or the collapse of over-sized stars directly into a medium-sized black hole. Both of these ideas require conditions that scientists think only existed in the first few hundred million years after the big bang.

The process suggested by the latest Chandra study can occur at any time in the universe's history, implying that intermediate-mass black holes can form billions of years after the big bang, right up to the present day.

The growth of black holes in dense star clusters might also explain the detection of gravitational waves by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) of some black holes with masses between about 50 and 100 times that of the Sun. Such black holes are not predicted by most models of the collapse of massive stars.

"Our work doesn't prove that runaway black hole growth occurs in star clusters," said Adi Foord, a co-author from Stanford University in Palo Alto, California "But with additional X-ray observations and extra theoretical modeling, we could make an even stronger case."

A paper describing these results was accepted and appears in The Astrophysical Journal. It is also available online.

NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory's Chandra X-ray Center controls science operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Media Contacts:

Megan Watzke

Chandra X-ray Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts

617-496-7998

mwatzke@cfa.harvard.edu