Chandra Discoveries in 3D Available on New Platform

Your browser does not support the video tag.

![]() More Information

More Information

Credit: VR version: VR model: NASA/CXC/Brown Univ./A.Dupuis et al.;

Simulation: INAF/S. Ustamujic et al.; X-ray data: NASA/CXC/MSFC/D.Swartz et al.

A collection of the 3D objects from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory is now available on a new platform from the Smithsonian Institution. This will allow greater access to these unique 3D models and prints for institutions like libraries and museums as well as the scientific community and individuals in the public.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is one of NASA's Great Observatories (along with the Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, and Compton Gamma-ray Observatory). Chandra, the world's most powerful X-ray telescope, is operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts.

Chandra's 3D datasets are now included in Voyager, a platform developed by the Smithsonian's Digitization Program Office, which enables datasets to be used as tools for learning and discovery. Viewers can explore these fascinating 3D representations of objects in space alongside a statue of George Washington or a skeleton of an extinct mammoth.

Bubbles With Titanium Trigger Titanic Explosions

Astronomers using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory have announced the discovery of an important type of titanium, along with other elements, blasting out from the center of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas A). This new result, as outlined in our latest press release, could be a major step for understanding exactly how some of the most massive stars explode.

The different colors in this new image mostly represent elements detected by Chandra in Cas A: iron (orange), oxygen (purple), and the amount of silicon compared to magnesium (green). Titanium (light blue) detected previously by NASA's NuSTAR telescope at higher X-ray energies is also shown. These Chandra and NuSTAR X-ray data have been overlaid on an optical-light image from the Hubble Space Telescope (yellow).

Telescopes Unite in Unprecedented Observations of Famous Black Hole

Your browser does not support the video tag.

![]() More Information

More Information

Video compilation: NASA/GSFC/SVS/M.Subbarao & NASA/CXC/SAO/A.Jubett

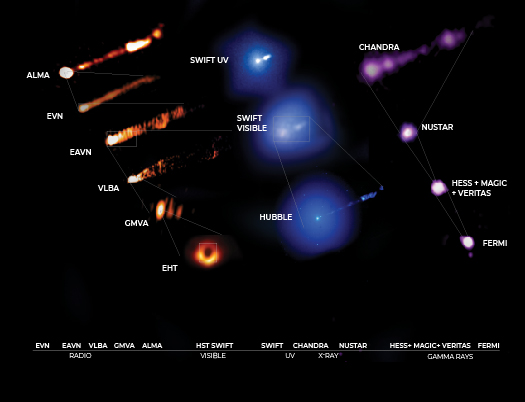

In April 2019, scientists released the first image of a black hole in the galaxy M87 using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). This supermassive black hole weighs 6.5 billion times the mass of the sun and is located at the center of M87, about 55 million light-years from Earth.

The supermassive black hole is powering jets of particles that travel at almost the speed of light, as described in our latest press release. These jets produce light spanning the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to visible light to gamma rays.

To gain crucial insight into the black hole's properties and help interpret the EHT image, scientists coordinated observations with 19 of the world's most powerful telescopes on the ground and in space, collecting light from across the spectrum. This is the largest simultaneous observing campaign ever undertaken on a supermassive black hole with jets.

The NASA telescopes involved in this observing campaign included the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Hubble Space Telescope, Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR), and the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope.

What We Found When We X-rayed Uranus

Affelia Wibisono

We are pleased to welcome Affelia Wibisono, who received her Masters degree in Physics from Royal Holloway, University of London in 2012, as our guest blogger. She worked as a science communicator at London’s Science Museum and the Royal Observatory Greenwich before starting her PhD in 2018 at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory (MSSL). Her research interests are in X-ray emissions from planets in our Solar System, in particular how and why Jupiter produces intense X-ray auroras.

Huge, violent and exotic objects in space such as black holes, supernovae and quasars are what usually come to mind when one thinks about X-ray astronomy. But it’s the more humble X-ray sources found closer to home that my research group and I want to know more about. Many things in our Solar System emit X-rays, such as the Sun, comets, moons and even Pluto. Astronomers have also detected X-rays from the four rocky planets, Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars, and from the gas giants Jupiter, and Saturn. However, efforts to find X-rays from Uranus in 2002 and 2017 were fruitless — or so we thought.

Data Sonification: Stellar, Galactic, and Black Hole

Your browser does not support the video tag.

This latest installment from our data sonification series features three diverse cosmic scenes. In each, astronomical data collected by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and other telescopes are converted into sounds. Data sonification maps the data from these space-based telescopes into a form that users can hear instead of only see, embodying the data in a new form without changing the original content.

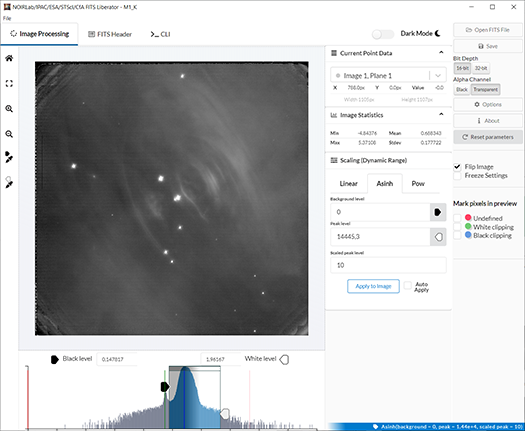

Upgrading Our Views of the Universe

How do we image our Universe? There are many different ways of translating information from the cosmos. But in working with scientific data and image processing software, you can create your own astronomy images from FITS files. "FITS," which stands for Flexible Image Transport System, is a digital file format used mainly by astronomers to work with data of cosmic objects. Today, we are happy to help announce an update to the open source FITS Liberator software that can be used to process your own astronomical data. —Kimberly Kowal Arcand (CfA)

Astronomy is predominantly a visual science. However, an important tool is needed to produce breathtaking color images from the observations made with telescopes such as the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, or the telescopes of NSF's NOIRLab at the international Gemini Observatory, Kitt Peak National Observatory, and Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. The key to unlocking those magnificent vistas is specialized image-processing software.

Cosmic Poetry Competition 2021: The Winners

We are delighted to again welcome Jonathan Taylor as a guest blogger. Jonathan is the author of several novels and poetry collections, the editor of several anthologies, and Associate Professor in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester in the UK.

I've always been fascinated by the intersections and overlaps between Creative Writing and science. It's always seemed to me that poetry and cosmology, for example, share a great many characteristics, in their methods and means of communication: they both play with, even bend, language; they both use metaphor and analogy; they both re-enchant and defamiliarize our universe, so we see it anew. Having written various poems over the years for Chandra X-Ray Observatory (in March 2010, June 2010, April 2012, and August 2016), I often find the poetry is already there, waiting to be discovered, in the language used to capture Chandra's amazing revelations.

Hence, as part of their course, we encourage our Creative Writing students at Leicester University to explore some of the fascinating overlaps between their writing and scientific research – including the work of NASA and Chandra X-Ray Observatory. Over the years, this has resulted in various student competitions (in December 2010: part one and part two; May and June 2012: part one and part two; February 2016, and February 2017). In January 2021, we held a new competition for student writers, in which they were again invited to submit poems that explore – directly or indirectly, literally or metaphorically – the language and findings from one of Chandra's press releases. You can read the two beautiful winning entries below: 'IC 4593' by Laura Sygrove, and 'A New Cosmic Triad of Sound' by Rebecca Hughes.

From NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to the Universe's Earliest Jet propulsion Laboratory

We are happy to welcome Thomas Connor as a guest blogger today. Thomas is a NASA Postdoctoral Fellow at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California and the author of a paper that is the subject of our most recent press release. He completed his undergraduate degree at Case Western Reserve University and earned his doctorate from Michigan State University. Prior to starting at JPL, Dr. Connor was a postdoctoral fellow at the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution for Science. His scientific interests include black holes in the dawn of the Universe, the evolution of galaxies in dense environments, and the structure of the Cosmic Web.

Most of the fundamental questions of astronomy relate to how the universe as we observe it was assembled. From stars and planets to nebulae and galaxies, many of the investigations of astronomy come down to crafting a coherent narrative of formation and evolution. Currently, that narrative is struggling to be built in the early universe, where supermassive black holes with masses a billion times that of the Sun are seen only a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. The challenge here is that, while we can model ways for such massive objects to form and grow, compressing that growth into such a short time scale is much more difficult. As an analogy, it is not surprising that an author can write a novel, but it would be astounding if she could do so in only one day.

Black holes grow by eating their surroundings, but, contrary to the typical depiction of these objects, they do not suck. Rather, they slowly nibble their way through an "accretion disk," an orbiting disk of gas that acts as a buffet for the black hole. As more gas makes its way inward, this disk will get hot from all of the friction of particles rubbing together, and it will start glowing like a hot coal. This bright light will act like a strong wind, pushing away further gas from replenishing the disk. Thus, the black hole's feeding is self-limiting — if it eats too fast, it won't be able to restock the buffet, and so it will have to slow down. This fundamental limit is why we are puzzled at how such massive black holes can exist so early.

On the Hunt for a Hidden Neutron Star

Emanuele Greco

We are pleased to welcome Emanuele Greco as a guest blogger. Emanuele is the first author of a paper describing the possible discovery of a neutron star left behind by supernova 1987A. Emanuele received a master’s degree in Physics at the University of Palermo in 2017. He is now completing his PhD in Astrophysics at the same University, where he is expected to defend his thesis next June. He spent six months of his PhD at the Anton Pannekoek Instituut of the University of Amsterdam. Emanuele’s main research interests deal with the X-ray spectroscopy of supernova remnants and objects embedded within their shells, with a particular focus on the different processes that generate X-ray emission.

Imagine having a bright and small light bulb and putting it behind a thick wall made of elements like iron and silicon. No light stemming from the bulb would be observed, because it is completely obscured by the wall. This quite simple scenario is perfectly suited also for the elusive compact object of supernova (SN) 1987A, which was investigated by scientists from University of Palermo (UniPa), INAF-Observatory of Palermo (OAPa), Astrophysical Big Bang Laboratory (RIKEN) and University of Kyushu.

SN 1987A is the only naked-eye SN observed since telescopes were invented and offers a unique opportunity to watch a SN evolving into a supernova remnant (SNR) in this time of multi-wavelength and multi-messenger observatories simultaneously at work. This event was particularly important because neutrinos emitted from an exploding star were detected on Earth for the first time. This discovery implies that the core of the progenitor star must have collapsed producing a shock wave — similar to the sonic boom from a supersonic plane — that ejected part of the stellar material into the surrounding environment. As a result, a compact object such as a neutron star, a relic of the stellar core, should have formed in the very heart of SN 1987A. However, despite the continuous monitoring performed at almost all wavelengths since the SN was detected, no clear indication for this compact object has been found so far. Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain this non-detection, such as the formation of a black hole instead of a neutron star.

Rare Blast's Remains Discovered in Milky Way Center

Astronomers have found evidence for an unusual type of supernova near the center of the Milky Way galaxy, as reported in our latest press release. This composite image contains data from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory (blue) and the NSF's Very Large Array (red) of the supernova remnant called Sagittarius A East, or Sgr A East for short. This object is located very close to the supermassive black hole in the Milky Way's center, and likely overruns the disk of material surrounding the black hole.

Researchers were able to use Chandra observations targeting the supermassive black hole and the region around it for a total of about 35 days to study Sgr A East and find the unusual pattern of elements in the X-ray signature, or spectrum. An ellipse on the annotated version of the images outlines the region of the remnant where the Chandra spectra were obtained.