General

Why Make Sonifications of Astronomical Data?

Jingle, Pluck, and Hum: Sounds from Space

Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)

When you travel to a foreign country where they speak a language you do not understand, it is usually imperative that you find a way to translate what is being communicated to you. In some respects, the same can be said about data collected from objects in space.

A telescope like NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory captures X-rays, which are invisible to the human eye, from sources across the cosmos. This high-energy light gets sent back down to Earth in the form of ones and zeroes. From there, the data are transformed into a variety of different things — from plots to spectra to images.

This last category — images — is arguably what most telescopes are best known for. For most of astronomy's long history, however, most who are blind or visually impaired (BVI) can often not fully experience the wonders that telescopes have captured.

In recent decades, that has begun to change. There are various ways that astronomers, data scientists, astronomy communication professionals, and others can work with communities of different abilities, from creating 3D prints and visual descriptions to sound-based products. As part of the Chandra X-ray Center and NASA's Universe of Learning, a team of experts led by Dr. Kimberly Arcand has been working to "sonify" (turn into sound) data from some of NASA's greatest telescopes.

Chandra Discoveries in 3D Available on New Platform

Your browser does not support the video tag.

![]() More Information

More Information

Credit: VR version: VR model: NASA/CXC/Brown Univ./A.Dupuis et al.;

Simulation: INAF/S. Ustamujic et al.; X-ray data: NASA/CXC/MSFC/D.Swartz et al.

A collection of the 3D objects from NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory is now available on a new platform from the Smithsonian Institution. This will allow greater access to these unique 3D models and prints for institutions like libraries and museums as well as the scientific community and individuals in the public.

The Chandra X-ray Observatory is one of NASA's Great Observatories (along with the Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer Space Telescope, and Compton Gamma-ray Observatory). Chandra, the world's most powerful X-ray telescope, is operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Massachusetts.

Chandra's 3D datasets are now included in Voyager, a platform developed by the Smithsonian's Digitization Program Office, which enables datasets to be used as tools for learning and discovery. Viewers can explore these fascinating 3D representations of objects in space alongside a statue of George Washington or a skeleton of an extinct mammoth.

Upgrading Our Views of the Universe

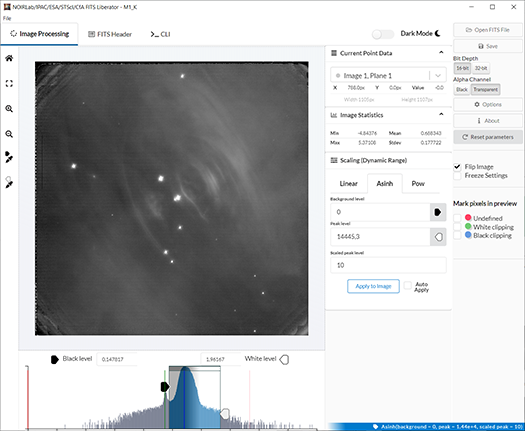

How do we image our Universe? There are many different ways of translating information from the cosmos. But in working with scientific data and image processing software, you can create your own astronomy images from FITS files. "FITS," which stands for Flexible Image Transport System, is a digital file format used mainly by astronomers to work with data of cosmic objects. Today, we are happy to help announce an update to the open source FITS Liberator software that can be used to process your own astronomical data. —Kimberly Kowal Arcand (CfA)

Astronomy is predominantly a visual science. However, an important tool is needed to produce breathtaking color images from the observations made with telescopes such as the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, or the telescopes of NSF's NOIRLab at the international Gemini Observatory, Kitt Peak National Observatory, and Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. The key to unlocking those magnificent vistas is specialized image-processing software.

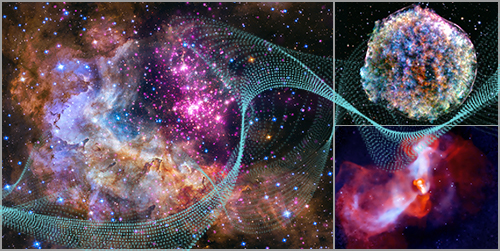

Data Sonification: A New Cosmic Triad of Sound

Your browser does not support the video tag.

A new trio of examples of 'data sonification' from NASA missions provides a new method to enjoy an arrangement of cosmic objects. Data sonification translates information collected by various NASA missions — such as the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Hubble Space Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope — into sounds.

This image of the Bullet Cluster (officially known as 1E 0657-56) provided the first direct proof of dark matter, the mysterious unseen substance that makes up the vast majority of matter in the Universe. X-rays from Chandra (pink) show where the hot gas in two merging galaxy clusters has been wrenched away from dark matter, seen through a process known as "gravitational lensing" in data from Hubble (blue) and ground-based telescopes. In converting this into sound, the data pan left to right, and each layer of data was limited to a specific frequency range. Data showing dark matter are represented by the lowest frequencies, while X-rays are assigned to the highest frequencies. The galaxies in the image revealed by Hubble data, many of which are in the cluster, are in mid-range frequencies. Then, within each layer, the pitch is set to increase from the bottom of the image to the top so that objects towards the top produce higher tones.

Welcome to Emily Zhang, Chandra Summer Intern

Emily Zhang on the Athabasca Glacier in Banff National Park in Canada. Emily traveled there in the summer of 2018, coincidentally just after finishing her first research project at the CfA! Credit: Emily Zhang

We are delighted to introduce Emily Zhang, who is working as a summer intern in the Chandra X-ray Center at the Center for Astrophysics. Emily is spending half of her time working on astronomy research with Dr Pat Slane and half working on science communication with us in the Chandra Communications and Public Engagement group. She is an undergraduate at Columbia University majoring in astrophysics and (hopefully) concentrating in political science. We asked Emily some questions about her background and interests in astronomy and science communication.

How did your interest in astronomy develop?

I remember watching the TV show Nova with my parents when I was little, and thinking that outer space looked so beautiful and so different from the rest of the world I knew. I also remember going on trips to my local planetarium (the Hayden Planetarium at the Museum of Science in Boston) growing up, and coming out of their shows crying at how big the universe was. I have a vivid memory of checking out a book on black holes for kids from the library, and reading that if you went through a black hole, you could end up in a new universe with up to 11 dimensions. This was not something I understood at all as a 4th grader, but I was impressed.

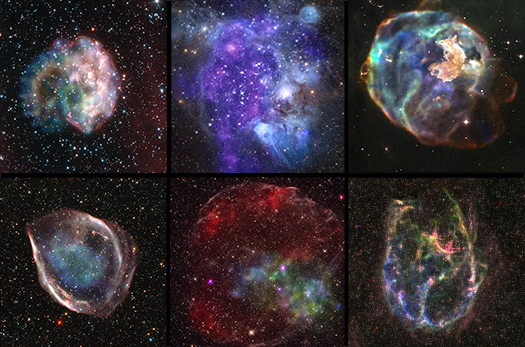

Behind the Scenes with the Image Makers

Credit: Enhanced Image by Judy Schmidt (CC BY-NC-SA) based on

images provided courtesy of NASA/CXC/SAO & NASA/STScI.

It is both an art and a science to make images of objects from space. Most astronomical images are composed of light that humans cannot detect with their eyes. Instead, the data from telescopes like NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory are “translated,” so to speak, into a form that we can understand. This process is done following strict guidelines to ensure scientific accuracy while trying to achieve the highest levels of aesthetics possible.

Over the two decades of the Chandra mission, we have had many talented people who have been involved with making our publicly-released images. We interviewed our current team and share some of their answers to questions posed to all of them below. Kim Arcand is Chandra’s visualization lead and has been with the mission since before launch; Nancy Wolk has been involved with Chandra’s data analysis, software, and spacecraft science operations before joining the image processing team; Lisa Frattare spent years making images from the Hubble Space Telescope before switching career gears but continues to lend her expertise part-time to Chandra’s efforts; Judy Schmidt is a citizen scientist who spends some of her free time using public data to make gorgeous images of space, including those featured in our latest release.

Exploring New Paths of Study with Chandra

Illustration: Chandra X-ray Observatory

We make progress in astrophysics in a variety of ways. There is the sort that starts along a defined path, driven by meticulous proposals for telescope time or detailed science justifications for new missions. The plan is to advance knowledge by traveling further than others, or clearing a broader path. And then there are others.

A big mission like NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory begins with plans for investigation along a slew of different directions and lines of study. At the time of Chandra's launch on July 23rd, 1999, scientists thought these paths would mainly follow studies of galaxy clusters, dark matter, black holes, supernovas, and young stars. Indeed, in the last 20 years we've learned about black holes ripping stars apart (reported eg in 2004, 2011 and 2017), about a black hole generating the deepest known note in the universe, about dark matter being wrenched apart from normal matter in the famous Bullet Cluster and similar objects, about the discovery of the youngest supernova remnant in our galaxy, and much more.

New Chandra Operations Control Center Opens

Chandra's New Operations Control Center

A new state-of-the-art facility that will operate NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory has opened. This new Operations Control Center, or OCC, will help Chandra continue its highly efficient performance as NASA's premier X-ray observatory.

As the name suggests, the OCC controls the operation of the Chandra spacecraft while it is in orbit, as scientists and engineers design plans for efficiently and safely observing its targets.

Two years before Chandra's launch into space in 1999, NASA awarded the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory a contract to establish the first OCC as part of the Chandra X-ray Center, under the direction of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. Northrup Grumman was and continues to be a prime contractor for Chandra, employing many staff members at the OCC.

Chandra to Continue Operations During US Government Shutdown

NASA has designated Chandra as "excepted" during the Government shutdown and requested that SAO continue Chandra X-ray Center (CXC) operations. Since NASA is unable to provide funding during the shutdown, the Smithsonian Institution has agreed to advance funding to continue science and mission operations through mid-March, as necessary.