Listen to This Month's "Planet Parade" with NASA's Chandra

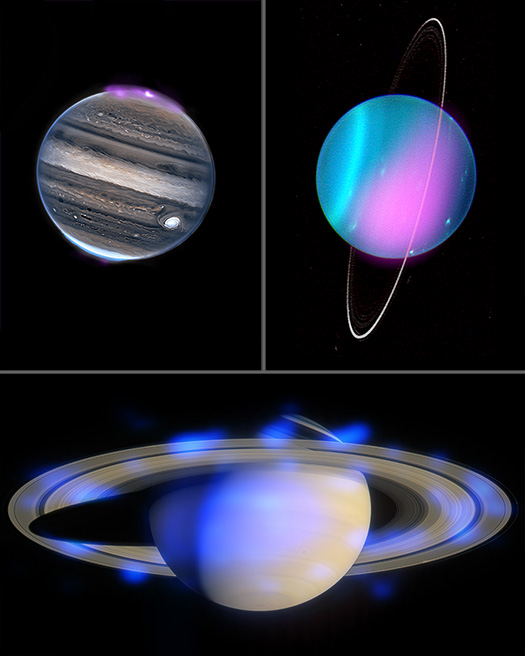

The Planets Jupiter, Uranus, and Saturn

More images, videos, and information

Sonification Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)

In late February, people in the Northern Hemisphere can look up for a special sight: Six planets will all be visible from clear and dark night skies. New sonifications from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory released Wednesday will help commemorate this latest “planetary parade.”

Because the planets in our solar system travel around the Sun in the same plane (known as the ecliptic), they will sometimes appear bunched together in the sky when their orbits find them on the same side of the Sun at the same time. When this happens, it looks like the planets have roughly formed a line from our vantage point on Earth.

In Chandra’s sonifications, which translate astronomical data into sound, three of the planets that will be on display — Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus — can be seen and heard in ways that they cannot from Earth.

Young "Sun" Caught Blowing Bubbles by NASA's Chandra

HD 61005

More images, videos, and information

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/John Hopkins Univ./C.M. Lisse et al.; Infrared: NASA/ESA/STIS; Optical: NSF/NoirLab/CTIO/DECaPS2;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

This image contains the first astrosphere, or wind-blown bubble, that astronomers have captured surrounding a star that is a younger version of our Sun. This discovery was made using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and is described in our latest press release.

The astrosphere was found around a star called HD 61005, which is located only about 120 light-years from Earth. HD 61005 has roughly the same mass and temperature as the Sun but is much younger with an age of about 100 million years, compared to the Sun’s age of about 5 billion years. This commonality with the Sun is important because the Sun has a similar bubble, which scientists call the heliosphere. The discovery of the astrosphere around HD 61005 gives astronomers a chance to study a structure that may be similar to what the Sun was embedded in several billion years ago.

A Cosmic Heart Where New Stars Thrive

Cocoon Nebula

More images and information

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Infrared: NASA/JPL/Caltech(WISE); Optical: M. Adler, B. Wilson;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/L. Frattare

To celebrate Valentine's Day, we are releasing a new image of the Cocoon Nebula (officially named IC 5146). This heart-shaped nebula is a region in the Milky Way galaxy where new stars are forming. X-ray data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory (red, green, and blue) reveal a cluster of new stars that are just poking through the stunning nebula. Young stars, like those in the Cocoon Nebula, are very active and give off large amounts of X-rays that Chandra can detect.

Celebrate the 'AstrOlympics' During the Winter Games in Italy

The ‘AstrOlympics’ project connects the amazing physical feats of the athletes competing in the Olympic Games to the spectacular physical phenomena discovered by NASA and other telescopes in space.

By comparing examples of speed, acceleration, time, mass, rotation, density, and more of athletes on the ground to objects in space, viewers of AstrOlympics may find new appreciation and inspiration from both.

The AstrOlympics project, which runs for both the Summer and Winter Games, has been celebrating cosmic and athletic triumphs since 2016. It was conceived of and developed by the science center for NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which is operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory on behalf of NASA.

NASA Telescopes Spot Surprisingly Mature Cluster in Early Universe

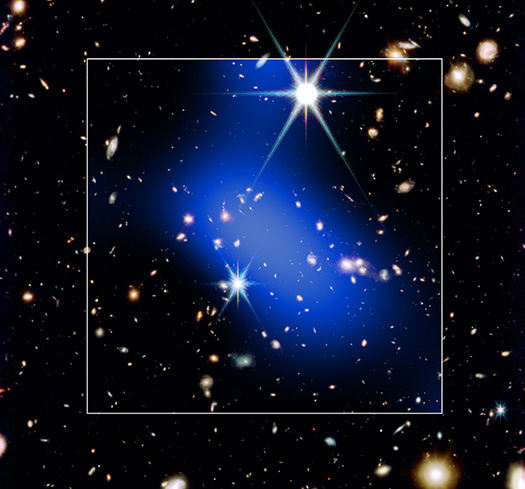

Protocluster JADES-ID1

More images, videos, and information

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/CfA/Á Bogdán; Infrared (JWST): NASA/ESA/CSA/STScI;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/P. Edmonds and L. Frattare

This graphic represents the discovery of what may be the most distant protocluster ever found, as described in our latest press release. By using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory together with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have netted an important piece in the history of the universe: when galaxy clusters, the largest structures held together by gravity, begin to form.

The main panel contains an infrared image from the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES), a deep infrared imaging project that used more than a month of the telescope’s observing time. The white box outlines X-rays (blue) seen with Chandra.

NASA's Chandra Releases Deep Cut From Catalog of Cosmic Recordings

Sagittarius A*

More images, videos, and information

Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/N. Wolk

Like a recording artist who has had a long career, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory has a “back catalog” of cosmic recordings that is impossible to replicate. To access these X-ray tracks, or observations, the ultimate compendium has been developed: the Chandra Source Catalog (CSC).

The CSC contains the X-ray data detected up to the end of 2020 by Chandra, the world’s premier X-ray telescope and one of NASA’s “Great Observatories.” The latest version of the CSC, known as CSC 2.1, contains over 400,000 unique compact and extended sources and over 1.3 million individual detections in X-ray light.

Within the CSC, there is a wealth of information gleaned from the Chandra observations — from precise positions on the sky to information about the the X-ray energies detected. This allows scientists using other telescopes — both on the ground and in space including NASA’s James Webb and Hubble Space Telescopes — to combine this unique X-ray data with information from other types of light.

The richness of the Chandra Source Catalog is illustrated in a new image of the Galactic Center, the region around the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy called Sagittarius A*. In this image that spans just about 60 light-years across, a veritable pinprick on the entire sky, Chandra has detected over 3,300 individual sources that emit X-rays. This image is the sum of 86 observations added together, representing over three million seconds of Chandra observing time.

A Scientist’s Journey: Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

Nicole Kuchta, Communications, Education and Engagement intern at NSF NOIRLab. Photo Credit: NOIRLab

Our guest blogger today is Nicole Kuchta. Nicole Kuchta is a Communications, Education and Engagement intern at NSF NOIRLab. She specializes in astronomy writing and content creation, having also worked with the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and NASA’s Universe of Learning.

Every day our Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, but one day in the (very) distant future things will change. The stars in our universe, including our Sun, live for a finite period, and eventually die.

Right now, in the Sun’s core, hydrogen fuses together to form helium, letting out heat and light. In about 5 billion years, however, the Sun will run out of hydrogen. It will expand to a phase that astronomers call a red giant: a cooler and larger star combining atoms to form heavier and heavier elements. At this stage, the Sun will expand to swallow Mercury, Venus, and then, likely, our Earth.

When the Sun completely runs out of fuel, its glowing outer layers of gas will waft away into a vivid, airy, hot cloud called a planetary nebula. In the core of this ghostly structure will sit the remainder of the once-living Sun: a white dwarf. The Sun at this point will become a ball of carbon under intense pressure and heat, like a ghostly diamond in the sky. It’ll be half the Sun’s original mass packed into a sphere about the size of Earth.

All this might sound like the plot of a sci-fi movie, but it’s anything but fiction. How do we know the future of our Sun? Scientists have studied stars for decades, developing and testing ideas as new data becomes available. This field of study is what astrophysicists call stellar evolution, or the journey of stars’ lives.

The story of Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar — a theoretical astrophysicist who revolutionized what we know about stellar evolution and namesake of the Chandra X-ray Observatory — helps explain how we arrived at our current understanding.

Supernova Remnant Video From NASA's Chandra Is Decades in Making

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant

More images, videos, and information

X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS

A new video shows changes in Kepler’s Supernova Remnant using data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory captured over more than two and a half decades with observations taken in 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2025. In this video, which is the longest-spanning one ever released by Chandra, X-rays (blue) from the telescope have been combined with an optical image (red, green, and blue) from Pan-STARRS.

Kepler’s Supernova Remnant, named after the German astronomer Johannes Kepler, was first spotted in the night sky in 1604. Today, astronomers know that a white dwarf star exploded when it exceeded a critical mass, after pulling material from a companion star, or merging with another white dwarf. This kind of supernova is known as a Type Ia and scientists use it to measure the expansion of the Universe.

NASA's Chandra Rings in New Year With Champagne Cluster

Champagne Cluster

More images, videos, and information

Credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/UCDavis/F. Bouhrik et al.; Optical:Legacy Survey/DECaLS/BASS/MzLS;

Image Processing: NASA/CXC/SAO/P. Edmonds and L. Frattare

Celebrate the New Year with the “Champagne Cluster,” a galaxy cluster seen in this new image from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and optical telescopes.

Astronomers discovered this galaxy cluster Dec. 31, 2020. The date, combined with the bubble-like appearance of the galaxies and the superheated gas seen with Chandra observations (represented in purple), inspired the scientists to nickname the galaxy cluster the Champagne Cluster, a much easier-to-remember name than its official designation of RM J130558.9+263048.4.

Cosmic Holiday Greetings From NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory

NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory is sending out a holiday card with four new images of cosmic wonders. Each of the quartet of objects evokes the winter season or one of its celebratory days either in its name or shape.

Chandra’s seasonal greetings begin with NGC 4782 and NGC 4783, a pair of colliding galaxies when oriented in a certain way resembles a snowman. The top and bottom of the snowman are each elliptical galaxies, separated by a distance of about 30,000 light-years. The galaxies, seen in an image from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (gray), are bound together through gravity. X-rays from Chandra (purple) show a bridge of hot gas between the two galaxies, like a winter scarf.